PUBLICATION INFORMATION

Russell Thomas, The Guardian

There is now so much ocean plastic that it has become a route for invasive species, threatening native animals with extinction

There is now so much ocean plastic that it has become a route for invasive species, threatening native animals with extinction

Japan’s 2011 tsunami was catastrophic, killing nearly 16,000 people, destroying homes and infrastructure, and sweeping an estimated 5m tons of debris out to sea.

That debris did not disappear, however. Some of it drifted all the way across the Pacific, reaching the shores of Hawaii, Alaska and California – and with it came hitchhikers.

Nearly 300 different non-native species caught a lift across the ocean in what can be thought of as a “mass rafting” event. The Smithsonian Environmental Research Center in 2017 counted 289 Japanese marine species that were carried to distant shores after the tsunami, including sea snails, sea anemones and isopods, a type of crustacean.

Plastic rafting poses a huge and mostly unknown danger. Invasive species that ride plastic litter to new shores can reduce habitats for native species, carry disease (micro-algae is a particular threat), and put further strain on ecosystems already pressured by overfishing and pollution. According to David Barnes, marine benthic ecologist at the British Antarctic Survey and visiting lecturer at Cambridge University, rafting increases “extinction risk [while] reducing biodiversity, ecosystem function and resilience”.

A striped beakfish swims in a water-filled box onboard a Japanese boat that washed ashore in Washington state, US. Five of the fish survived hitching a ride across the Pacific. Photograph: Allen Pleus/AP

The tsunami also showed something new: many of the animals survived more than six years adrift, longer than previously thought possible.

Rafting – or oceanic dispersal – is a natural phenomenon. Marine organisms attach themselves to marine litter and travel hundreds of kilometres. Free-floating clumps of seaweed such as sargassum, sometimes 3 metres thick, provides a home for certain “rafting species” in the Atlantic, such as reef fish, or pipefishes and seahorses, which are both poor swimmers.

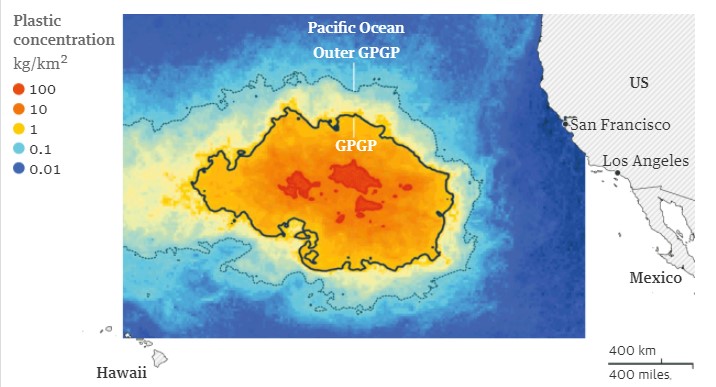

2018 estimate of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, which disperses plastic litter to the remotest corners of the planet. Graphic: Guardian

But while it is relatively rare for a non-native species to successfully survive in a new environment, the huge increase in waste being dumped at sea, as well as abandoned fishing gear, enables biofouling: aquatic organisms attaching themselves where they are not wanted.

This turns “a rare, sporadic evolutionary process into a quotidian one”, says Prof Bella Galil, curator at Steinhardt Museum of Natural History, Tel Aviv University. Invasive species can threaten biological diversity, food security and human wellbeing. Sea grapes from Australia arriving in the Mediterranean in 1990, for example, displaced other marine algae – setting off a domino effect that ultimately led to a reduction in native gastropods and crustaceans.

One of the most potent corridors for marine invasions is from the Red Sea, via the Suez canal, into the Mediterranean. Galil notes that of 455 marine alien species currently listed in the eastern Mediterranean, most are thought to have come through the canal, thanks to the prevailing northward current or via ballast water, hitching a ride mostly on plastics.

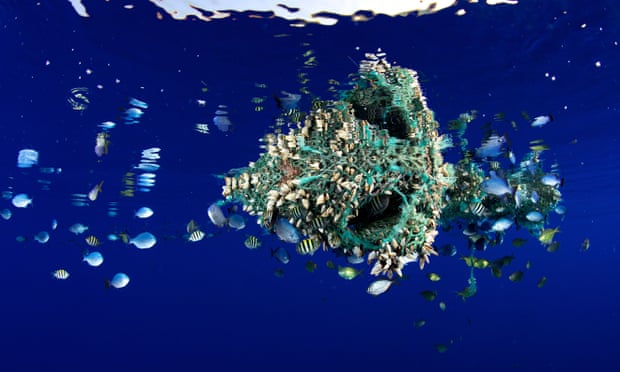

Ocean debris floating off Hawaii has become home to many fish and invertebrates.

Photograph: Bryce Groark/Alamy

These invasive species do not just hang around. Many have spread into the central and western Mediterranean, again often colonising floating litter. As well as adversely affecting critical habitats, Galil says, some are “noxious, poisonous, or venomous and pose clear threats to human health”. Long-spined sea urchins and nomad jellyfish, both venomous and both native to the Indian Ocean, are just two examples now causing damage in the Mediterranean.

The route is likely to become even more popular after the widening of the canal, Egypt’s response to the grounding of the container ship Ever Given earlier this year. “Larger canal, larger vessels [will mean] likely larger volume of Red Sea species arriving in the Mediterranean,” Galil says.“Plastic, particularly, has massively increased the transport possibilities in terms of how much flotsam there is, its variety (in size and structure), where it goes and how long it floats for,” he says. “Furthermore, plastic can increase local spread of invader species when they do arrive and establish.” One compilation from 2015 listed 387 species, from micro-organisms to seaweeds and invertebrates, found to have rafted on marine litter, in “all major oceanic regions”.